Embryonic editing: Controversial game changer

Science could bring that option to our doorsteps in the not-so-distant future, and many Americans are divided about whether embryonic gene editing, as it is known, is a good idea, according to the Pew Research Center.

Half of those surveyed recently said they would not want to use gene editing to lower their baby’s chances of developing a major ailment, for example. But 48 percent would use the new technology to do this. Those with stronger religious convictions were more likely to say they were against such treatment.

The Pew Center points out that there are other possibilities too. Could a designer baby be smarter and stronger? Embryonic gene editing is already controversial, and it is not yet an option for ambitious parents. But what is it and how was it developed? Here is the rundown, along with links for further study:

The beginning: The complete set of all human genes is known as the "genome." The Human Genome Project, a research program aimed at mapping all genes in human beings, was launched 26 years ago, according to the National Human Genome Research Institute. It was completed in April 2003.

That project “revealed that there are probably about 20,500 human genes,” according to the institute’s website. “This ultimate product of the HGP [Human Genome Project] has given the world a resource of detailed information about the structure, organization and function of the complete set of human genes. This information can be thought of as the basic set of inheritable 'instructions' for the development and function of a human being.”

An important discovery: Francisco Mojica, a scientist at the University of Alicante in Spain, characterized the CRISPR locus in 1993, according to the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT in Massachusetts. CRISPR stands for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats. It is an immune system discovered in bacteria.

Mojica's research continued, and by 2005 he and other scientists were developing an understanding of CRISPRs' function. “He proposed that CRISPRs serve as part of the bacterial immune system, defending against invading viruses,” the website explains. “They consist of repeating sequences of genetic code, interrupted by “spacer” sequences -- remnants of genetic code from past invaders. The system serves as a genetic memory that helps the cell detect and destroy invaders (called ‘bacteriophage’) when they return.”

He and other researchers hypothesized that CRISPR is “an adaptive immune system.” From there, researchers during the past decade have gradually pushed the ball forward.

Continuing research: By focusing on this road map to the human body, scientists are discovering new ways to treat illness. In July, for example, National Institutes of Health researchers announced that they had “identified and tested a molecule that shows promise as a possible treatment for the rare Gaucher disease and the more common Parkinson's disease.”

A breakthrough: In a 2012 paper in the journal Science, Emmanuelle Charpentier, director of the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in Germany, and Jennifer Doudna, professor of chemistry and molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley, demonstrated that “the mechanism used by bacteria to disable their foes could be adapted as a programmable precision genetic tool to modify genes in cells and organisms,” according to the UNESCO website. Earlier this year, the organization gave both women the l’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science award.

Another step: In 2013, the first method to engineer CRISPR to edit the genome in mouse and human cells was published by Feng Zhang, a bioengineer at the Broad Institute and MIT, according to the institution's website.

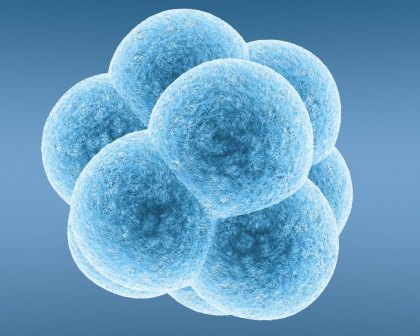

Why is it controversial? In 2015, Chinese researchers reported using the technology to edit human embryos.The International Society for Stem Cell Research subsequently called for a moratorium on embryonic gene editing, "as scientists currently lack an adequate understanding of the safety and potential long term risks of germline genome modification." The organization also said that a "deeper and more rigorous deliberation on the ethical, legal and societal implications of any attempts at modifying the human germ line is essential if its clinical practice is ever to be sanctioned."

This year: In April, Chinese researchers reported using the technology to edit nonviable human embryos in an effort to make them resistant to HIV infection, according to the journal Nature.

Below: A video on CRISPR by the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT.

To know more:

- Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT: Questions and answers about CRISPR.

- Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT: CRISPR timeline.

- The International Society for Stem Cell Research: The International Society for Stem Cell Research Has Responded to the Publication of Gene Editing Research in Human Embryos.

- National Institutes of Health-National Human Genome Research Institute: All about the Human Genome Project.

- NIH-National Human Genome Institute: An Overview of the Human Genome Project.

- NIH-National Human Genome Institute: Researchers make advance in possible treatments for Gaucher, Parkinson's diseases.

- Nature: Second Chinese team reports gene editing in human embryos.

- Pew Research Center: Many Americans are wary of using gene editing for human enhancement, Aug. 26, 2016.

- Springer Link: CRISPR-Cas 9 mediated gene editing in human tripronuclear zygotes, May 2015.

- UNESCO: Reinventing genetic research.

Related:

Millions linked to Genghis Khan

If you would like to comment, give us a shout, or like us on Facebook and tell us what you think.