-- Betsy R., Suwanee, Georgia

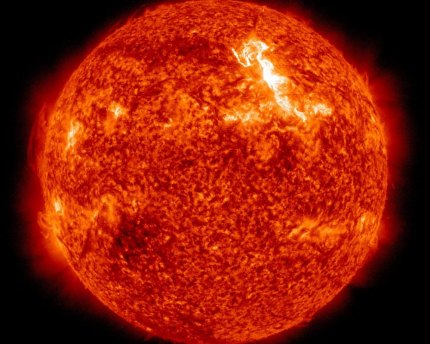

Solar storms have been in the news lately, but the truth is these naturally occurring solar flares and coronal mass ejections from the sun happen all the time—or at least a few hundred times a year from what we can tell here on Earth. CMEs are caused by large-scale magnetic eruptions from the sun that send particles into the atmosphere at high speeds. But luckily for us the only threats these solar storms pose within the Earth’s atmosphere are to our technology.

Harmful radiation from these flares can’t pass through Earth's atmosphere to physically affect humans on the ground; however, when intense enough they can disturb the atmosphere in the layer where communications signals travel, according to NASA. Both CMEs and solar flares, if powerful enough, have this disrupting effect.

“When a CME strikes Earth’s atmosphere, it causes a temporary disturbance of the Earth’s magnetic field,” reports Deborah Byrd, editor of the EarthSky.org website. “The charged particles can slam into our atmosphere, disrupt satellites in orbit and even cause them to fail, and bathe high-flying airplanes with radiation.”

Besides disrupting navigation and telecommunications systems, solar storms can also cause electricity blackouts down below. One example happened in Quebec on March 13, 1989. A particularly strong CME caused a power failure that stretched across Quebec and parts of the northeastern United States, blacking out the region for nine hours and affecting 6 million people in the process.

The technological effects of solar storms can be worrisome, but scientists can track and predict these storms to mediate their potential negative impacts on a region. Additionally, one positive result of solar storms in places that lie at higher latitudes is the appearance of the radiant aurora borealis (also known as the Northern Lights) during these phenomena.

While there have been plenty of solar storms lately, this year actually marks a low-point for such activity—a so-called solar minimum—in the solar cycle. The Space Weather Prediction Center of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts that the next peak of solar activity will be in July 2025.

Amateur astronomers interested in tracking solar storms should check out SpaceWeatherLive.com, a nonprofit, all-volunteer project in Belgium that coordinates information from several websites on a range of topics including astronomy, space, aurora and related subjects. One of the site’s cool features is a free glimpse into the last three days of solar storm activity hitting the Earth’s atmosphere.

If you would like to become more involved in the process of tracking solar storms, the Solar Stormwatch II project led by the University of Reading in England looks for volunteers to help record data. Volunteers can virtually aid the project by observing CME data and imagery on the project’s website and recording/outlining what they see.

Related:

NASA observatory captures image of solar flare

This column was reprinted with permission. EarthTalk is produced by Roddy Scheer and Doug Moss and is a registered trademark of the nonprofit Earth Action Network. To donate, visit www.earthtalk.org. Send questions to: question@earthtalk.org.

Like us on Facebook and tell us what you think.