700-year-old tea jar a work of art

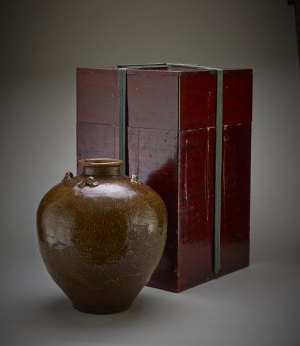

Tea-leaf storage jar named Chigusa and its storage box. -- Courtesy Freer Gallery of Art.

The Smithsonian Institution’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery will host the renowned tea jar Feb. 22–July 27 in an exhibit titled “Chigusa and the Art of Tea.”

Chigusa was one of countless utilitarian ceramics crafted in southern China during the 13th or 14th century. It was shipped to Japan as a container for a commercial product and once there was used as tea-leaf storage jar, which endowed it with a special status. Over time, the jar became a prized antique. As a sign of additional respect, it was given a personal name: Chigusa, which means “thousand grasses” or “myriad things,” an evocative phrase from Japanese poetry.

In 16th century Japan, “chanoyu,” or the “art of tea,” evolved into a major aesthetic and cultural pastime. Influential tea connoisseurs imbued high status to “meibutsu,” or celebrated objects, through such practices as naming, adorning and close observation. Tea diaries kept by these enthusiasts recorded detailed descriptions of Chigusa’s physical attributes and accessories, allowing contemporary scholars to see the jar through their eyes.

Joining Chigusa in the Sackler Gallery’s exhibit are other cherished objects, including calligraphy by Chinese monks, Chinese and Korean tea bowls and Japanese stoneware water jars and wooden vessels used during this formative time of Japanese tea culture. The exhibition space recreates a Japanese tea room, complete with tatami mats.

“Tea men looked at Chigusa and found beauty even in its flaws, elevating it from a simple tea jar to how we know it today,” said Louise Allison Cort, curator of ceramics at the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. “This ability to value imperfections in objects made by the human hand is one of the great contributions of Japanese tea culture to the world.”

The documentation and artifacts that surround Chigusa — including inscriptions, letters, ceremonial accessories and storage boxes — reveal the history of ownership and enjoyment. Few jars with comparable documentation survive in Japan or elsewhere.

Marks on the jar’s base are thought to be the signatures of its owners, dating from the 15th to the 16th centuries. The jar later became the property of the Tokugawa shogunate and then was owned by private Japanese collectors before being acquired by the Freer Gallery at auction in 2009.

For display in the tea room, Chigusa was outfitted with luxury accessories added by its successive owners: a mouth covering of antique Chinese gold-brocaded silk, a netted bag of sky-blue silk and a set of blue silk cords used to tie ornamental knots attached to the four lugs on the jar’s shoulder. A video in the exhibition follows a tea master dressing Chigusa in its adornments, an elaborate process.

Visitors will be able to experience a traditional Omotesenke tea presentation March 23 and April 6, including the preparation of matcha, the whisked green tea made from leaves of the kind that Chigusa would have contained.

Other public programs include a conversation with core Chigusa researchers Oka Yoshiko and Andrew M. Watsky on March 2, and lunchtime curator-led tours April 3 and 10.

Chigusa will travel to the Princeton University Art Museum in the fall, where it will be on view Oct. 11–Feb. 1, 2015.

“Chigusa is the rare object that allows us deep insight into how people in Japan looked at, thought about and valued things over time,” said Watsky, professor of Japanese art history at Princeton. “We are incredibly fortunate to participate in the now centuries-long activity of examining and appreciating this singular ceramic jar.”

Chigusa was one of countless utilitarian ceramics crafted in southern China during the 13th or 14th century. It was shipped to Japan as a container for a commercial product and once there was used as tea-leaf storage jar, which endowed it with a special status. Over time, the jar became a prized antique. As a sign of additional respect, it was given a personal name: Chigusa, which means “thousand grasses” or “myriad things,” an evocative phrase from Japanese poetry.

In 16th century Japan, “chanoyu,” or the “art of tea,” evolved into a major aesthetic and cultural pastime. Influential tea connoisseurs imbued high status to “meibutsu,” or celebrated objects, through such practices as naming, adorning and close observation. Tea diaries kept by these enthusiasts recorded detailed descriptions of Chigusa’s physical attributes and accessories, allowing contemporary scholars to see the jar through their eyes.

Joining Chigusa in the Sackler Gallery’s exhibit are other cherished objects, including calligraphy by Chinese monks, Chinese and Korean tea bowls and Japanese stoneware water jars and wooden vessels used during this formative time of Japanese tea culture. The exhibition space recreates a Japanese tea room, complete with tatami mats.

“Tea men looked at Chigusa and found beauty even in its flaws, elevating it from a simple tea jar to how we know it today,” said Louise Allison Cort, curator of ceramics at the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. “This ability to value imperfections in objects made by the human hand is one of the great contributions of Japanese tea culture to the world.”

The documentation and artifacts that surround Chigusa — including inscriptions, letters, ceremonial accessories and storage boxes — reveal the history of ownership and enjoyment. Few jars with comparable documentation survive in Japan or elsewhere.

Marks on the jar’s base are thought to be the signatures of its owners, dating from the 15th to the 16th centuries. The jar later became the property of the Tokugawa shogunate and then was owned by private Japanese collectors before being acquired by the Freer Gallery at auction in 2009.

For display in the tea room, Chigusa was outfitted with luxury accessories added by its successive owners: a mouth covering of antique Chinese gold-brocaded silk, a netted bag of sky-blue silk and a set of blue silk cords used to tie ornamental knots attached to the four lugs on the jar’s shoulder. A video in the exhibition follows a tea master dressing Chigusa in its adornments, an elaborate process.

Visitors will be able to experience a traditional Omotesenke tea presentation March 23 and April 6, including the preparation of matcha, the whisked green tea made from leaves of the kind that Chigusa would have contained.

Other public programs include a conversation with core Chigusa researchers Oka Yoshiko and Andrew M. Watsky on March 2, and lunchtime curator-led tours April 3 and 10.

Chigusa will travel to the Princeton University Art Museum in the fall, where it will be on view Oct. 11–Feb. 1, 2015.

“Chigusa is the rare object that allows us deep insight into how people in Japan looked at, thought about and valued things over time,” said Watsky, professor of Japanese art history at Princeton. “We are incredibly fortunate to participate in the now centuries-long activity of examining and appreciating this singular ceramic jar.”

Taken from a Smithsonian Institution press release.