This morning, The Washington Post reported that Michael Flynn, national security adviser, had spoken to a Russian ambassador before the election. A spokesman for President Donald Trump told the paper Flynn had called to wish the ambassador happy holidays – which would not have been a violation of law. Other sources said the discussion involved sanctions imposed on Russia because of alleged interference in the U.S. election. Through a spokesman, Flynn said he couldn't recall whether the subject of sanctions had arisen.

Questions about the Logan Act were also voiced in 2015, when U.S. House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, invited Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to speak about Iran before a joint session of Congress.

Netanyahu had spoken to Congress before. But the invitation prompted some commentators to speculate about whether Boehner had violated the Logan Act.

The Logan Act dates to the administration of the second U.S. president, John Adams.It was signed into law 218 years ago -- Jan. 30, 1799. But what is the Logan Act? And why do we have it? Here is the rundown:

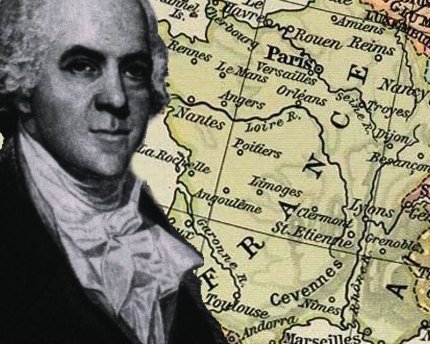

Why is it called the Logan Act? The law was named for Dr. George Logan (1753-1821), a senator from Pennsylvania who served from 1801 to ’07. Logan, a Quaker, was a member of what was then called the Democratic Republican Party. (Adams was a Federalist.) The senator came from a well-known family: His grandfather, James Logan, served as secretary to William Penn.

Background: France, an ally during the Revolutionary War, had its own revolution and a change of government as the 18th century drew to a close. Soon, France's relationship with the U.S. soured. French leaders were not happy about the Jay Treaty (1794) -- an attempt to settle lingering issues between the U.S. and Great Britain. By 1796, the French had begun seizing American merchant ships.

Adams sent Charles Pinckney, John Marshall and Elbridge Gerry on a diplomatic mission to France, but their efforts unraveled when three French representatives of Prime Minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand demanded a $250,000 bribe for Talleyrand and a $10 million loan for France before normalizing relations. (In dispatches, the French representatives were referred to as X, Y and Z, and this became known as the XYZ Affair.) The Americans refused the bribes.

What Logan did: War preparations began. But in 1798, Logan -- acting on his own and without government authority -- went to France and began negotiations.

Logan carried with him a certificate of citizenship from Thomas Jefferson, then vice president. He was well-received in France, recounts a 2006 Congressional Research Service report for Congress, Conducting Foreign Relations Without Authority: The Logan Act. The French government freed American ships and seamen and lifted the embargo on merchant ships.

Logan returned to the U.S. with the message that France wanted to settle the dispute and called upon Secretary of State Timothy Pickering. In his book, John Adams, (Simon & Schuster, 2001), David McCullough writes that Pickering “gave him short shrift and showed him to the door.” George Washington also refused to see Logan.

Adams invited Logan in and listened, McCullough writes.

But Adams also wrote this in a letter to the Senate on Dec. 12, 1798:

“Although the officious interference of individuals without public character or authority is not entitled to any credit, yet it deserves to be considered whether that temerity and impertinence of individuals affecting to interfere in public affairs between France and the United States, whether by their secret correspondence or otherwise, and intended to impose upon the people and separate them from their Government, ought not to be inquired into and corrected.”

In January 1799, Congress passed the Logan Act, which Adams signed into law.

What does the Logan Act say? “Any citizen of the United States, wherever he may be, who, without authority of the United States, directly or indirectly commences or carries on any correspondence or intercourse with any foreign government or any officer or agent thereof, with intent to influence the measures or conduct of any foreign government or of any officer or agent thereof, in relation to any disputes or controversies with the United States, or to defeat the measures of the United States, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than three years, or both.

“This section shall not abridge the right of a citizen to apply, himself or his agent, to any foreign government or the agents thereof for redress of any injury which he may have sustained from such government or any of its agents or subjects.”

Impact: The law is known among public officials. Even so, it sometimes doesn't deter well-meaning individuals from taking matters into their own hands. In fact, it didn't stop George Logan. A biography on the U.S. Congress website recounts that despite the strongest possible message -- a new law on the books all because of him -- Logan "went to England in 1810 on a private diplomatic mission as an emissary of peace, but was not successful."

What do you think? Did Flynn or Boehner violate the law? Tell us on Facebook.

Quick Study was compiled by StudyHall.Rocks editors using these references:

- 2006 Congressional Research Service report for Congress, Conducting Foreign Relations Without Authority: The Logan Act.

- Miller Center, University of Virginia: American President, a reference resource-- John Adams.

- U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian, The XYZ Affair and the Quasi-War with France, 1798–1800.

- The American Presidency Project, University of California, Santa Barbara, John Adams, message in reply to the Senate.

- Biographical Directory of the United States Congress: George Logan.

Books:

- The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents, by William A. DeGregorio, (Barricade Books; 1993).

- John Adams, by David McCullough, (Simon & Schuster; 2001).

See this and other animations on cartoontruth.com.

Related:

Quick Study: The Complicated John Adams

If you would like to comment, give us a shout, or like us on Facebook and tell us what you think.