Voting rights -- past, present and future

From poll taxes to the more recent voter ID laws, the issue has been on the American agenda throughout the country's history:

1787, The Constitutional Convention: Delegates arrive with different ideas about what qualifies someone to vote. Most state constitutions require voters to own property, writes Catherine Drinker Bowen in Miracle at Philadelphia, The story of the Constitutional Convention May to September 1787 (Back Bay Books; 1966).

States are left to set qualifications for elections to the House of Representatives and Senate. The convention sets no property qualifications for federal officeholders.

1803-1806, Corps of Discovery: The Lewis and Clark expedition, searching for a water route to the Pacific Ocean, includes York, a slave of Capt. William Clark. At one point, the explorers debate where to spend the winter. They decide to take a vote. York and a Native American woman, Sacagawea, are each allowed to vote. York is considered the first African-American man allowed to vote in the U.S., and Sacagawea, the first woman.

1819: The Panic of 1819, a financial crisis, leads to a popular movement to end property requirements for voting and office holders, according to Winning the Vote: A History of Voting Rights, on the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

1828: By this time, many states have extended male suffrage to non-property owners -- as long as they are white and male. The expansion of voting rights helps elect Andrew Jackson president.

1848, Women's Rights Convention at Seneca Falls, New York: More than 300 men and women gather to discuss women’s suffrage. Frederick Douglass, an activist and freed slave, is among the attendees.

Feb. 25, 1869: The House of Representatives passes the 15th Amendment to the Constitution by a vote of 144-44, according to the Library of Congress website. The amendment states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color or previous condition of servitude.”

Feb. 26, 1869: The Senate passes the 15th Amendment, 39 to 13.

Dec. 10, 1869: Separately, John Campbell, governor of the Wyoming Territory, approves a law granting women the right to vote. Women of the Wyoming Territory are also given rights "to the elective franchise and to hold office." (See the Library of Congress website.)

Feb. 3, 1870: Five years after the Civil War ends, the 15th Amendment is ratified. Despite the new law, Southern states use poll taxes and literacy tests to stop African-Americans from voting. These practices continue for 95 years.

June 4, 1919: Congress approves the 19th Amendment, guaranteeing women the right to vote. It is ratified Aug. 18, 1920.

1920: This marks the first national election in which women can vote. Republican Warren G. Harding, a newspaper publisher, beats another newspaper publisher, Democrat James M. Cox. The New York Times reports that suffrage did not double the vote and that 1 in 3 women exercised their new right.

1940: Attempts to keep African-Americans from voting are largely successful. By 1940, only 3 percent of eligible African-Americans in the South are registered to vote, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

Feb. 18, 1965: Jimmie Lee Jackson, 26, an African-American, is shot in the stomach by an Alabama state trooper during a civil rights protest in Marion, Alabama. Jackson, who would die eight days later, had been attempting to protect his mother, according to the Stanford University website, Martin Luther King and the Global Freedom Struggle.

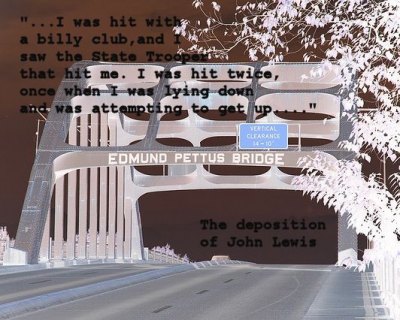

March 7, 1965: Led by John Lewis, a founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (now a congressman), approximately 600 protesters attempting to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, are attacked by authorities. The New York Times reports that Alabama state troopers and volunteer officers of the Dallas County Sheriff’s Office use “tear gas, night sticks and whips” to enforce Gov. George Wallace’s order against the Selma-to-Montgomery march. At least 17 demonstrators are hospitalized; 40 others are treated for injuries and tear gas inhalation. The Times reports that protestors “fought back with bricks and bottles.” Later, Lewis refutes this in a deposition, saying there was “no act of violence or any type of retaliation … on the part of any of the demonstrators.”

March 9, 1965: Martin Luther King Jr. leads a symbolic march with approximately 2,000 clerics to the bridge, where they kneel in prayer. Later that night, several white residents of Selma attack James Reeb, a white Unitarian minister from Massachusetts. Reeb, 38, dies two days later. King delivers the eulogy at his memorial service, according to the Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography.

March 21: Approximately 3,200 protestors – an integrated crowd led by King – begin walking from Selma to Montgomery.

March 25: King leads the nonviolent protestors to the Capitol steps in Montgomery. By this time, 25,000 protestors are part of the crowd.That night, four Ku Klux Klan members spot Viola Gregg Liuzzo, 39, in a car with an African-American man, 19-year-old Leroy Moton. The two are headed to Montgomery to pick up demonstrators waiting for transportation back to Selma, according to the Encyclopedia of Alabama, a service of Alabama universities. Liuzzo, a Detroit housewife who had come to Alabama to work for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, had been driving marchers back and forth from Montgomery to Selma.

Klan members give chase, eventually shooting and killing Liuzzo. Moton, covered in her blood, manages to survive by pretending to be dead.

Aug. 6, 1965: President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The act prohibits voting practices or procedures that discriminate on the basis of race. One section of the Voting Rights Act requires some jurisdictions to get preclearance from specific federal authorities in Washington before enacting voting procedures. The act defines "covered jurisdictions" as states or political subdivisions that "maintained tests or devices as prerequisites to voting and had low voter registration or turnout," according to Cornell University Law School’s Legal Information Institute. The preclearance requirement is to expire after five years. (The act was subsequently reauthorized several times.)

2006: The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is again reauthorized for 25 years. The coverage formula is not changed.

2010: After the 2010 midterm elections, legislators in various states introduce laws that make it more difficult to vote, recounts the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law. Some states set up stringent voter ID laws. Voting rights advocates propose laws to increase access to voting. (See the Center’s analysis.)

June 25, 2013: In Shelby County, Alabama, v. Holder, Attorney General, the Supreme Court rules that part of the Voting Rights Act is unconstitutional: “Its formula can no longer be used as a basis for subjecting jurisdictions to preclearance.”

2014: A bipartisan group of representatives propose the Voting Rights Amendment Act of 2014, an attempt to devise a new formula to protect voting rights. It is referred to a subcommittee.

2015: The Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies releases a report noting that since 1965 the black-white gap in voter turnout has decreased dramatically. Also, more people of color have been elected. Even so, people of color remain underrepresented in office, the report says.

Quick Study was compiled by YT&T editors using these sources:

- Miracle at Philadelphia, The story of the Constitutional Convention May-to-September 1787 (Back Bay Books; 1966).

- Winning the Vote: A History of Voting Rights, by Steven Mintz, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

- National Park Service: Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail --York

- Library of Congress: 15th Amendment to the Constitution.

- National Archives: 19th Amendment to the Constitution-- Women's right to vote.

- Women's Rights National Historical Park --New York.

- Library of Congress: Voting Rights for Women, by Cheryl Lederle

- The American Civil Liberties Union: Timeline, a History of the Voting Rights Act

- Stanford University website, Martin Luther King and the Global Freedom Struggle.

- The National Park Service, Selma-to-Montgomery March National Historic Trail.

- Encyclopedia of Alabama, a service of Alabama universities.

- The National Archives: Confrontations for Justice -- John Lewis deposition.

- Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography.

- Shelby County v Holder: Supreme Court of the United States blog.

- Shelby County v Holder: Cornell University Law School, Legal Information Institute.

- Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies: 50 Years of the Voting Rights Act.

- U.S. Department of Justice: The Voting Rights Act of 1965.

- Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law: Voting Laws Roundup 2014.

Recommended:

National Council of State Legislators: Voter Identification Requirements

Related: