Surface shifts on Europa similar to Earth

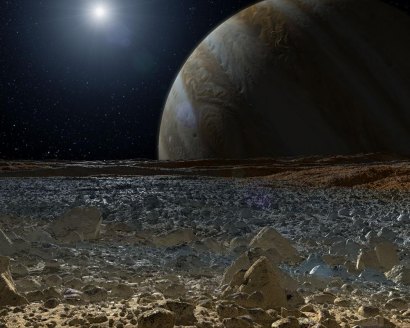

Artist's concept of Europa, one of Jupiter's moons. Image: NASA.

This is the first sign of surface-shifting geological activity on a world other than Earth.

Plate tectonics is a theory that Earth's outer layer is made up of plates or blocks that move, which is why mountains and volcanoes form and earthquakes happen, according to NASA.

Now, researchers have clear visual evidence of Europa’s icy crust expanding, but they could not find areas where the old crust was destroyed to make room for the new. While examining Europa images taken a decade ago by NASA’s Galileo orbiter, planetary geologists Simon Kattenhorn, of the University of Idaho, Moscow, and Louise Prockter, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, discovered some unusual geological boundaries.

“We have been puzzled for years as to how all this new terrain could be formed, but we couldn’t figure out how it was accommodated,” said Prockter. “We finally think we’ve found the answer.”

The surface of Europa -- one of Jupiter’s four largest moons and slightly smaller than Earth’s moon -- is riddled with cracks and ridges. Surface blocks are known to have shifted in the same way blocks of Earth's outer ground layer on either side of the San Andreas fault move past each other in California. Many parts of Europa’s surface show evidence of extension, where bands miles wide formed as the surface ripped apart and fresh icy material from the underlying shell moved into the newly created gap, a process akin to sea-floor spreading on Earth.

Scientists studying Europa often reconstruct the moon’s surface blocks into their original configuration -- as with a jigsaw puzzle -- to get a picture of what the surface looked like before the disruption occurred. When Kattenhorn and Prockter rearranged the icy terrain in the images, they discovered that about 7,700 square miles (about 20,000 square kilometers) of the surface were missing in the moon’s high northern latitudes.

Further evidence suggested the missing terrain moved under a second surface plate -- a scenario commonly seen on Earth at plate-tectonic boundaries.

The team’s results appear in the online edition of the journal Nature Geoscience.

Related: