We may soon see whether the 113th Congress, just beginning the second year of its two-year term, can accomplish more in 2014 than it did in 2013. That’s a low bar for success.

Last year, Congress passed just 72 bills, the smallest total since at least the end of World War II. On most issues of any substance, lawmakers were unable to bridge deep divisions between Republicans and Democrats, the House and the Senate.

They have been able to come together on one major issue during the new year: a spending bill that funds federal agencies in 2014 (the bare minimum required of Congress). Another test is likely to come this week when the Senate is expected to approve a House-passed farm bill (which replaces legislation that expired in September). Success is still in doubt for other major items: immigration, the financial soundness of Social Security and Medicare, tax reform, the minimum wage, international trade, climate change and more.

All those issues jammed up in gridlock can make a U.S. citizen wistful for the days of the first Congress (1789-91), which was able to compromise on such weighty issues as the location of the nation’s capital, payment of debts incurred during the Revolutionary War and the establishment of a judicial system.

But were those really the good old days? Were the founding members of Congress more civil and open to compromise than today’s politicians? Could party passions be controlled when momentous decisions were up for debate?

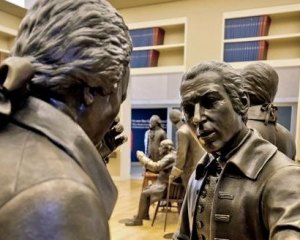

Those questions were the subject of two discussions last fall in Virginia at Mount Vernon’s Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington. The participants were Douglas Bradburn, the library’s founding director; Edward Larson, a historian and law professor at Pepperdine University in Malibu, Calif., and James Kirby Martin, a history professor at the University of Houston.

They shared their views in two videos produced around the time of the partial government shutdown Oct. 1-16 as Congress squabbled over legislation to provide funding for the fiscal year that began Oct. 1. The videos are: “Excessive party spirit — How might our Founding Fathers view today’s political troubles?” and “Government in the 1790s— All Politeness and Compromise?” Edited transcripts are below, but first let’s set the stage for the presentations.

The prelude

After the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, it established the structure for a new government in the Articles of Confederation, a document that was approved Nov. 15, 1777, and had to be ratified by all 13 states, a process completed March 1, 1781.

The government had fewer powers under the Articles of Confederation than it does today. The confederation Congress — a single legislative body, rather than the two-chamber House and Senate — could not levy taxes, place tariffs on imports or regulate commerce, even commerce national in scope. State legislatures were directed to fund the confederation government by levying taxes based on the value of land and buildings in the state, but Congress lacked the power to enforce that provision.

Congress could declare war, enter into treaties, establish a currency (however, states could have their own currencies too), borrow money, spend money, determine the size of the military (however, those forces would have to come from state regiments) and appoint a commander in chief. But Congress could not do those things unless nine of the 13 state delegations, 70 percent, agreed. Less consequential legislation could be approved with a simple majority.

Additionally, each state had to send at least two but no more than seven delegates to Congress, yet got only one vote on legislation.

Thus, some of the hardest decisions facing Congress required first a consensus of two to seven people within the state delegations and then 70 percent approval overall. Sometimes that was a tough task.

There was a president of Congress, elected from the membership, and committees to manage the government, but no separate executive branch.

The Articles of Confederation did not last long. They were replaced with the U.S. Constitution, approved Sept. 17, 1787, by a convention of delegates from 12 of the 13 states. George Washington presided over the convention. The document, which required nine states for ratification, passed that threshold June 21, 1788.

The first Congress under the Constitution took office March 4, 1789. Washington was inaugurated president on April 30, with John Adams as vice president and a Cabinet that included Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. The first Congress had 65 members of the House and 26 senators.

There were no formal political parties then, but during Washington’s presidency, differing views of government began to coalesce into two camps, one led by Jefferson, the other by Hamilton. Jefferson’s followers became the Democratic-Republican Party, and Hamilton’s belonged to the Federalist Party.

Here the some major positions of the parties during their early years:

Federalist Party: believed in a broad interpretation of government powers under the Constitution, wanted a strong executive branch, promoted government support for manufacturing, sought high tariffs on imports, successfully argued for the creation of a central bank, supported a professional, permanent national military force.

Democratic-Republican Party: believed in a strict interpretation of the Constitution to limit federal power, wanted more power to reside in the legislative rather than in the executive branch, emphasized agrarian interests, fought for low tariffs, tried to kill the central bank, opposed a standing army in peacetime, preferring to rely on state militias.

This is an edited condensation of the two October discussions that Bradburn conducted with Larson and Martin.

Discussion 1

Bradburn: Right now the government is shut down, and a lot of people have been wondering, what would the founders think about all of this?

Larson: This is just the sort of activity that troubled Washington. I’m working now on a book on Washington’s role in founding the new republic during the 1780s. And one of the reasons he was willing to come out, reluctantly, of retirement was he saw gridlock in our country. He saw that the confederation Congress was not working. They weren’t able to get through necessary legislation, necessary reforms to keep our country going.

The country he loved was being torn apart into individual states, which he thought would become the playthings of the European powers, would lack that vitality and vigor that could create a strong economy. And he was very concerned about the economic drift of the country. He pushed forming the Constitution to erect a structure that could get over that gridlock and get things done for all the people.

Martin: I think the founders would be very, very concerned because they very much believed in trying to solve problems. One of the greatest characteristics of George Washington was that rather than being a great ideologue, he was a problem solver. That’s one reason he was very successful in the end as a general. He knew how to bring people together. He knew how to get those individuals to try to come to some sort of a consensus. He would get his generals together in council meetings during the Revolutionary War, and he brought that same sort of a concept to the presidency.

He surrounded himself with talented individuals, not necessarily because they agreed but because they probably were among the very best minds available to him. Now those individuals, as we look into the decade of the 1790s, will start fighting among themselves. They will find all sorts of things to disagree about, whether it’s funding the national debt, establishing a national bank, [or] putting subsidies into manufacturing to try to build the national economy.

They will fall apart and disagree, but in the end there’s enough sense of unity there that they indeed will do the best they can to solve the problems rather than letting the whole process break down.

Bradburn: It’s always dangerous to ask a historian to get into the head of someone who lived in a very different time. But what we can see right away is that the founders were obsessed with the problem of party. None of them liked it in the abstract, but all of them participated in it in different parts of their lives. These guys, after all, were revolutionaries and were willing to fight for their principles to the death. But when we look at the 1790s and George Washington as a man who was able to stand above party, deal with an administration going in multiple directions and still get things done, we see a guy who worked very hard to try to bring civility and some decency to American politics.

Ultimately the legacy he left was in his farewell address, in which he directly warned the country of the dangers of excessive party spirit. In particular he used analogies of combustion and the danger of this burning heat of passions being drawn into party spirit. He thought if we swung from one party to the other it would fatigue the country so much that they would look to an individual leader to come in and really produce a despotism. The danger of party was one of the messages that Washington left the country, and I think he would be extremely dissatisfied of the state that we have right now.

Discussion 2

Bradburn: The 1790s represent some of the great compromises in American political history as the government is being put together, as the great talents are being marshaled by Washington in his administrations, but also represents the birth of partisan politics and really party politics. [James] Madison and Jefferson moved to create a popular interest, a popular faction, a popular party against Hamilton to stop his successes in Congress.

Then by the end of the decade you’ve got a situation in which partisan politics is so strong that the Adams administration is threatening to muzzle the opposition with the power of the federal government with the Alien and Sedition Acts [which enabled the government to fine or imprison people who made “false, scandalous and malicious” statements about the president or Congress].

On the other hand, you are getting popular opposition to these acts, arguing that they are null and void because they are considered to be unconstitutional. Who can decide what’s unconstitutional? It’s still an open question in the 1790s. Is it the legislative branch? Is it the people? Is it the Supreme Court? It might be all three of those things. And so what you see is gridlock, not unlike what you have today, and often backed up with threats of civil war. So it was not always a model for the best way that representative popular politics can function.

Larson: As Doug has noted, it was not all sweetness and light in the 1790s. That was the period where the political parties emerged. They emerged over sincere differences of opinion. Washington tried desperately to bridge those differences, pull together a Cabinet that would reflect a variety of different constitutional viewpoints and tried to work together to build consensus to push the country forward.

Martin: I’ve read a number of disparaging comments about Washington, his ambition of wanting to become president, written by various individuals, sort of cranky types from various states; also, [some people claimed] he wanted the federal capital as close to his property as he could so he could make big bucks on it. That relates to what was this very complex compromise of 1790 in terms of dealing with the national debt.So that kind of backbiting is just there. I think it’s part of the political process no matter when, where, why or how. But in terms of the matter of coming to compromise, I think there is some real success during the decade in trying as best individuals can to solve very, very difficult problems, probably more success on the domestic front—if you leave out the whiskey rebellion [resulting from a tax on liquor], which almost led to a shooting war out in western Pennsylvania, which is pretty extreme. And there’s a great deal of disagreement about the Jay Treaty [an attempt to resolve post-Revolution disputes with Great Britain] and other possible agreements with other nations.

But on the whole, I would rate it as a fairly successful decade in getting the young republic off to a really good start.

Can today's Congress get anything done? Tell us on Facebook.

Follow Chuck Springston on Twitter.

Related:

Senator, governor: Who makes the best president?