Was the Boston Massacre really a massacre?

The event, 245 years ago this week, was the culmination of escalating violence in Boston essentially brought on by taxes levied by the British crown and enforced by its army.

But by Webster’s definition, a massacre is “the act or an instance of killing a number of usually helpless or unresisting human beings under circumstances of atrocity or cruelty.” With that in mind, here is a rundown.

Background:

An economic weapon: Colonists objected to a series of taxes, especially the Townshend Acts of 1767, named for Charles Townshend, chancellor of the exchequer (treasurer of Great Britain). The acts taxed imported goods including glass, tea, lead, paint and paper, while also undercutting the authority of colonial assemblies.

"Townshend specified that some of the revenue would be used to pay the salaries of colonial governors, thereby rendering them immune to pressure from local assemblies," explains Thomas Fleming in the book, Liberty! The American Revolution (Viking; 1997).

Colonists famously fought taxes by boycotting goods. But not all protests were nonviolent. A group formed, calling itself the Sons of Liberty – a name inspired by a speech delivered in Parliament by an American sympathizer, Irish-born Col. Isaac Barre.

The Sons of Liberty used force and intimidation against customs officers charged with enforcing Parliament's taxes.

“When these hated men [customs officers] appeared in Boston, the Sons of Liberty turned out on moonless nights with blackened faces and white nightcaps pulled low around their heads. More than a few customs commissioners fled for their lives," writes David Hackett Fischer in Paul Revere’s Ride, (Oxford University Press; 1994). "On one occasion, a Boston merchant noted in his diary, 'Two commissioners were very much abused yesterday when they came out from the Publick dinner at Concert Hall…Paul Revere and several others were the principal Actors.’ ”

An in-your-face reaction: A British fleet sailed into Boston harbor on Sept, 30, 1768. The ship's cannon was pointed at the town, Fischer writes. Two regiments landed and marched into Boston.

1770:

A steady boil: On Feb. 22, 1770, a group of adults and children gathered at the store of a merchant thought to have broken the boycott.

Ebenezer Richardson, considered a Tory informer for British customs commissioners, attempted to defend the merchant by taking a musket and firing into the crowd. His shots killed Christopher Seider, 11. The boy’s death handed the revolutionaries a martyr.

Then, on March 2, there were scuffles involving British soldiers and rope-workers, according to the Massachusetts Historical Society.

The spark: On a cold night a few days later -- March 5, 1770 -- a group of young men taunted Pvt. Hugh White, a British soldier guarding the Customs House. White hit one of the men with his gun, and the man screamed, recounts the article, The Boston Massacre on the PBS.org website. This drew attention and brought more bystanders, who then began tossing ice, snow and oyster shells. Church bells rang – a signal that residents were needed to fight a fire. All at once, the colonists turned into a mob.

Meanwhile, reinforcements arrived under the command of Capt. Thomas Preston. In all, there were nine British soldiers.

Why did protestors -- armed with snowballs, ice, rocks and oyster shells -- take the risk of provoking armed professional soldiers?

Bottom line: They thought they could.

“Their courage, considerably reinforced by liquor, was based on the assumption that a British soldier could not fire on rioters before a magistrate had read the Riot Act, which authorized the army to restore the King’s peace,” Fleming writes in Liberty! The American Revolution.

At this point, the magistrates in Boston weren’t going to risk their safety by reading the Riot Act.

Again, the definition specifies that the victims are "usually helpless or unresisting human beings under circumstances of atrocity or cruelty.” The Boston mob was not unresisting.

To begin with, it was never proved that Capt. Preston gave an order to fire. In his book, Fleming offers this account of the incident: “Someone in the crowd struck a soldier with a club, knocking him to the ground. The man sprang to his feet and was struck by another club, thrown from a distance. He leveled his musket and pulled the trigger. Seconds later, the other members of the guard imitated him.”

The dead included Crispus Attucks, Samuel Gray, Samuel Maverick, James Caldwell and Patrick Carr. Attucks, an African-American, may be the most well-known and is sometimes identified as the first casualty of the Revolutionary War. (Ironically, Parliament repealed most of the hated Townshend Acts that very day.)

So technically, it wasn't a massacre, but the Sons of Liberty sought to portray it that way. Samuel Adams, cousin of John Adams, gathered depositions from Boston residents who swore citizens had been peaceful that night, Fleming writes.

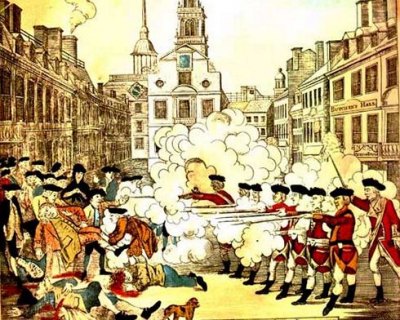

Within three weeks afterward, Revere produced an engraving that erroneously showed British soldiers firing simultaneously into the crowd, under the words, "The Bloody Massacre."

The day after the massacre, one lawyer agreed to represent the soldiers -- John Adams. Famously he got all but two of them off. Those two were branded on the thumbs. Given sentiments in Boston, how did Adams triumph?

Fleming paints a picture of Adams as a tenacious attorney. “First, he [John Adams] made a motion to try Preston and the enlisted men separately, which the court granted. Then he laboriously gathered depositions from dozens of people who portrayed a very different Boston from the one depicted by the Sons of Liberty.”

Witnesses reported “scores of men roaming the streets with cudgels in their hands, looking for soldiers to beat up."

But that wasn’t all. With the sheriff’s help, John Adams selected jurors “made up entirely of country people, who were unsympathetic to Boston’s brawlers,” Fleming writes.

Adams subsequently said his defense of those soldiers was “one of the best pieces of service I ever rendered my country.”

Writing under the name “Vindex,” Samuel Adams denounced the verdicts. But Fleming points out, “Privately, his friendship with John Adams became even more intimate. It would seem more than likely that Samuel Adams realized that without John Adams at the defense table, the evidence gathered on behalf of the British soldiers might have sent him and other members of the Liberty party to London under arrest for treason.”

In the biography, John Adams, David McCullough speculates, “Possibly Samuel Adams had privately approved, even encouraged it behind the scenes, out of respect for John’s fierce integrity and on the theory that so staunch a show of fairness would be good politics.”

Quick Study was compiled by YTT editors using these sources:

- Liberty! The American Revolution, by Thomas Fleming (Viking; 1997).

- John Adams, by David McCullough (Simon & Schuster; 2001).

- Paul Revere's Ride, by David Hackett Fischer (Oxford University Press; 1994)

- The Crispus Attucks Museum, created by the University of Massachusetts history club

- The Boston Massacre, PBS.org

- The Townshend Act of 1767, Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library.

- The Boston Massacre, the Massachusetts Historical Society

Related:

Quick Study: What was the Sugar Act?

Dec. 16, 1773: Behind the Boston Tea Party

If you would like to comment, contact us or like us on Facebook and tell us what you think.