Turn: Fighting women and the Revolution

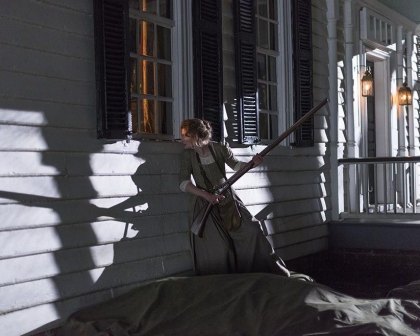

Take, for example, the story of Mary Woodhull, portrayed with gritty determination by Meegan Warner. In the most recent episode, the round-faced Colonial mother learns that her toddler’s life has been threatened and, frantic, attempts to kill one British officer before stabbing another to death.

The character is based on a historical figure, the wife of the Revolutionary War spy Abraham Woodhull.The real-life Mary Woodhull would not have faced this predicament. Abraham and Mary did not marry until 1781; this season is loosely based on events leading to Benedict Arnold’s betrayal and the execution of British spymaster John André in 1780.

No matter. More and more, the show’s writers have focused on women in danger -- crossing enemy lines to deliver messages, keeping secrets, listening into conversations, brandishing weapons, even plotting the next move. Prominently, Anna Strong (the convincing Heather Lind), originally a signal agent, is transitioning to a new job that is part adviser, part unpaid spymaster.

But while the plot is riveting in the well-acted show, is it also plausible? For context, here are examples of women who took part in the American Revolution, along with links for further study.

- Sarah Bradlee Fulton (1740-1835): A Bostonian, she is primarily known not for espionage but for coming up with the idea that the men in the Boston Tea Party should be disguised as Indians. At Bunker Hill, she was involved in nursing wounded soldiers. But her involvement in the war took a dangerous turn in March 1776, when Maj. John Brooks was looking for someone to deliver a message to Gen. George Washington, recounts the website for the Boston Tea Party Ship and Museum. Sarah Fulton agreed and successfully carried the message alone through enemy lines.

- Ann Bates (1748-): A Philadelphia schoolteacher turned British spy, Bates was married to a gun repairman in the British army and could identify weapons, according to the University of Michigan library website. Disguised as a peddler, she wandered among the troops in the Continental Army’s camp and effectively gathered information about supplies, weapons and manpower.

- Miss Jenny (unknown): A spy for the British, the woman known as “Miss Jenny” infiltrated French units fighting for the Americans, according to the University of Michigan website. Miss Jenny said she was looking for her father, who had gone from Canada to France years earlier. Captured and taken to the French camp by a guard who attempted to “force his amorous attentions” on her, she was later sent to Washington’s camp for questioning. She stuck to her story and was returned to the French, who cut her hair and released her. (The haircut was a sign of disgrace, but a man probably would have been executed.) Miss Jenny returned to the British and told them that Washington was going to attack New York in two places. Even so, “the American and French armies decided instead to use the French ships to transport their men from Chesapeake Bay to attack General Cornwallis' troops in Yorktown,” the website said. “The surrender of Lord Cornwallis in Yorktown, while Sir Henry Clinton and his army remained in New York, led to Sir Henry Clinton's disgrace and the eventual end of the Revolution.”

- Lydia Barrington Darragh (1728-1789): The British took over her house during the war, according to the National Women’s History Museum. When British officers ordered her family to stay in their bedrooms one evening, she hid in a closet and listened in as they planned a surprise attack on Washington’s army. Later, an officer knocked on the door to her bedroom and she answered, “pretending to have been asleep,” the museum’s website recounted. The next day she persuaded one of the British officers to give her a pass to get flour from the mill and visit her young children, living with relatives. After getting her flour, she continued on, headed for a tavern known to be a “message center” for colonists. While on her way, she ran into an officer for the Continental Army and passed on the message.

Links:

Boston Tea Party Ship and Museum, Sarah Bradlee Fulton.

Clements Library, University of Michigan: Miss Jenny.

Clements Library, University of Michigan: Ann Bates.

Journal of the American Revolution: Ann Bates, spy extraordinaire.

Related:

Turn's enablers: A spy's support group

Simcoe: Turn's British (Colonial) villain

Turn: Peggy Shippen as femme fatale

Fact, fiction and 'Turn,' the Colonial spy drama

'Turn' serves up revolutionary history

Turn: John Andre, melancholy spymaster

Turn: Robert Rogers, the perfect rogue

Men and women of the founding generation

If you would like to comment, give us a shout, or like us on Facebook and tell us what you think.