History colors Senate hearing

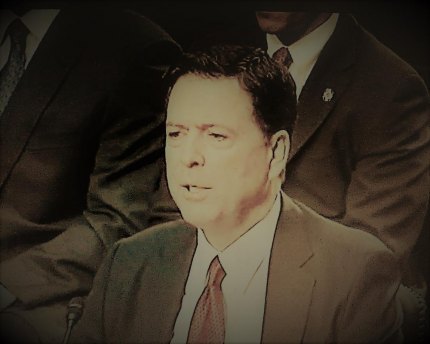

The testimony of former FBI Director James Comey June 8 before the Senate Intelligence Committee offered an odd but compelling history lesson.

Fired on May 9, Comey declined to answer numerous specific questions in open session about the FBI’s investigation into whether there was coordination between President Donald Trump’s campaign and Russian officials in connection with hacking during the 2016 presidential election. But at other times he and the senators spoke at length, sometimes making inside-baseball references. Here are four such exchanges, along with sources for further study:

1. The ghost of J. Edgar Hoover: Comey admitted that he informed Trump he was not personally under investigation. And under questioning, he explained the context:

“I was speaking to him and briefing him about some salacious and unverified material. It was in the context of that, that he [Trump] had a strong and defensive reaction about that not being true. And my reading of it was it was important for me to assure him we were not personally investigating him. And, so the context then was actually narrower, focused on what I just talked to him about. … I was very, very much about being in kind of a J. Edgar Hoover type situation. I didn’t want him thinking that I was briefing him on this to sort of hang it over him in some way. I was briefing him on it because we had been told by the media that it was about to launch. And we don’t want to be keeping it from him …. He needed to know this was being said. But I was very keen not to leave him with the impression that the bureau was trying to do something to him. And so that’s the context in which I said, ‘sir, we’re not personally investigating you.’”

Between the lines: J. Edgar Hoover served as FBI director from 1924 until his death in 1972. Under Hoover’s leadership, “the bureau grew in responsibility and importance, becoming an integral part of the national government and an icon in American popular culture,” recounts a biography on the FBI’s website.

But Hoover also “habitually used the FBI’s enormous surveillance and information-gathering powers to collect damaging information on politicians throughout the country,” according to the Encyclopedia Britannica website, “and he kept the most scurrilous data under his own personal control.”

2. The FBI’s tradition: The hearing often revolved around questions about Michael Flynn, the retired general who resigned as national security adviser following stories that he lied about discussing sanctions with the Russian ambassador to the United States. Comey recalled that during one meeting with Trump, the president said, "I hope you can see your way clear to letting this go, to letting Flynn go. He is a good guy. I hope you can let this go."

Comey responded only that Flynn was a good guy.

Following up on this exchange, Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, questioned Comey about why he didn’t attempt to educate the president. “You could have said: Mr. President, this meeting is inappropriate. This response could compromise the investigation,” Collins suggested. "You should not be making such a request. It is fundamental to the operation of our government that the FBI be insulated from this kind of political pressure."

Comey says he explained to Trump “why it is in his interest, and every president’s interest, for the FBI to be apart, in a way, because its credibility is important to the president and to the country.”

Between the lines: This exchange concerns the way our government systems work. Consider that the opposite of a nonpartisan FBI would be a weaponized FBI wielded by whichever political party happens to hold power.

In an opinion piece in The Washington Post, Barbara McQuade, a law professor at the University of Michigan Law School and the former U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan, wrote, “During my career as a prosecutor, I learned that independence is essential in law enforcement. The legitimacy of our justice system depends on public trust that criminal charges and investigations are based on a fair application of the law and not on a political agenda or ideology.”

3. Going medieval: Trump said he hoped Comey would let this (the investigation) go. And Sen. Angus King, I-Maine, latched onto the word hope. “When a president of the United States in the Oval Office says something like, I hope or I suggest or would you, do you take that as a directive?” King asked.

Yes, Comey responded. “It rings in my ears as kind of, ‘Will no one rid me of this meddlesome priest?’”

Brightening, King put in, “I was just going to quote that. In 1170, December 29, Henry the Second said, “who will rid me of this meddlesome priest?’ and the next day, he (Thomas of Becket) was killed. … It’s exactly the same situation. We’re thinking along the same lines.”

Between the lines: The famous line, as recounted by Comey -- “Will no one rid me of this meddlesome priest?”-- is delivered by Henry II in the stage play and classic movie, Becket.

Henry II became king of England in 1154. “Using his talented chancellor Thomas Becket, Henry began reorganizing the judicial system,” recounts the BBC’s history. “The Assize of Clarendon (1166) established procedures of criminal justice, establishing courts and prisons for those awaiting trial.”

But the relationship between the two deteriorated after Henry tried to exert more control over the church. Becket, by then the archbishop of Canterbury, refused to comply. According to the BBC, Henry exclaimed, “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?” (But meddlesome sounds better, doesn't it?)

Four knights “took his words literally and murdered Becket in Canterbury Cathedral in December 1170. Almost overnight Becket became a saint. Henry reconciled himself with the church, but royal control over the church changed little,” the BBC recounts.

4. The Logan Act: “Any suggestion that General Flynn had violated the Logan Act, I always find pretty incredible,” remarked Sen. Roy Blunt, R-Mo. “The Logan Act has been on the books for over 200 years. Nobody has ever been prosecuted for violating the Logan Act.”

Between the lines: The Logan Act dates to the administration of the second U.S. president, John Adams. Signed into law 218 years ago, the act was named for Dr. George Logan (1753-1821), a senator from Pennsylvania who served from 1801 to ’07. Logan is famous for traveling to France – without government approval – in an attempt to avert war.The act says this: “Any citizen of the United States, wherever he may be, who, without authority of the United States, directly or indirectly commences or carries on any correspondence or intercourse with any foreign government or any officer or agent thereof, with intent to influence the measures or conduct of any foreign government or of any officer or agent thereof, in relation to any disputes or controversies with the United States, or to defeat the measures of the United States, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than three years, or both."

But Blunt is right. Even Logan ignored the law. (See our story here.)

To know more:

- BBC History: Henry II (1133-1189).

- Encyclopedia Britannica: J. Edgar Hoover.

- FBI.gov: J. Edgar Hoover.

- Nixon Library.gov: Watergate trial conversations.

- The Washington Post, perspective: I worked with the FBI as a federal prosecutor; Trump is threatening the bureau's independence, by Barbara McQuade, May 10, 2017.

Related:

Quick Study: What is the Logan Act?

Follow StudyHall.Rocks on Twitter.

If you would like to comment, give us a shout, or like us on Facebook and tell us what you think.