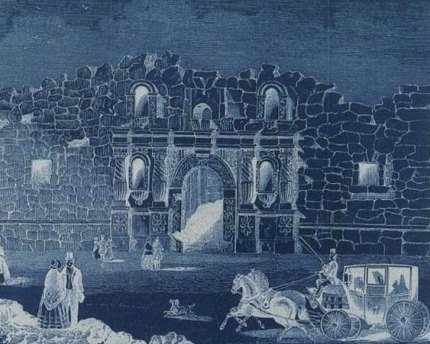

Misremembering the Alamo: The true story

But as frequently happens, the legend doesn’t always match the history. The battle of the Alamo is loaded with myths and folk tales.

One is that Davy Crockett went to Texas specifically to join the handful of men at the Alamo who were taking on the 1,600-man force of Gen. Antonia Lopez de Santa Anna in the struggle for independence from Mexico. He and the others at the Alamo, the story goes, were willing to fight to the death because they knew it would buy time for Texas Gen. Sam Houston to build the army that would eventually crush Santa Anna.

The anniversary of the battle is a good time to look at the true sequence of events that put Crockett at the Alamo in March 1836 and to see if the sacrifice of lives there really was a benefit to Houston’s military campaign.

Crockett’s journey to the Alamo

After Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821, it encouraged Americans to settle in the country’s largely uninhabited Texas region. One of the new arrivals was Houston, a former Tennessee governor who came to Texas in 1832, just as tensions and distrust were increasing between the Mexican government and American settlers who wanted more control over their affairs.

During a trip to Washington in April 1834 on business for a land speculation company, Houston met with friend Crockett, a member of Congress, writes historian William C. Davis in Three Roads to the Alamo: The Lives and Fortunes of David Crockett, James Bowie, and William Barret Travis (HarperCollins Publishers Inc., 1998)] Before that time, Crockett had never mentioned Texas in speeches or correspondence “even once,” Davis point out, but “within months it stole into his sentences repeatedly.”

In December 1834, Crockett, a fierce opponent of President Andrew Jackson and his chosen successor, Vice President Martin Van Buren, announced that rather than live under a Van Buren presidency he would leave the U.S. and head to the wilds of Texas. Clearly, Crockett had Texas on his mind well before the siege of the Alamo.

In an August 1835 election, Crockett lost his seat in Congress. His prospects dimmed for a future in Tennessee politics or a role on the national stage—Crockett had presidential aspirations. It seemed like a good time to make that trip to Texas, check out the land and maybe get involved in politics there.

The troubles in Texas boiled into war on Oct. 2, 1835, when American settlers fired on Mexican troops attempting to take a cannon from a Texas town.

On Nov. 1, Crockett and a small group of companions left West Tennessee for Texas. When Crockett departed in November he could not have been going to Texas to defend the Alamo, because at that time the fort was occupied by Mexican forces and the Texas rebels wouldn’t gain control of it until December.

The Texans set up a government that began meeting on Nov. 1 and made Houston a general in command of the new Texas army on Nov. 12. However, Houston had no authority over the volunteer units, such as the those who would gather at the Alamo, and could not issue orders to them.

Crockett crossed into Texas in mid-November. In early December, as he continued his journey into Texas, Crockett went on a leisurely, monthlong hunt and found a spot that he thought would be a good place to settle—hardly the actions of man rushing to a battle where he faced near-certain doom.

On Jan. 8, Crockett and his followers reached San Augustine, where—as at other stops on his journey—he was welcomed with much fanfare. He was a true celebrity of his time. Books written about and by him extolled his adventures as a frontiersmen and showed off his folksy humor. Citizens in San Augustine and elsewhere along his trail assumed he had come to join the revolution.

San Augustine leaders asked Crockett to be a candidate to represent them at a constitutional convention set for March 1 at Washington-on-the-Brazos. Crockett was attracted to the idea but feigned disinterest, as politicians seeking to appear humble are wont to do.

Davis writes: “He had come to Texas to fight, not to seek office, he told them disingenuously, for getting involved in the rebellion formed no part of his original intention.” But Crockett had now “committed himself for the first time publicly to going into the volunteer forces,” which had the side benefit, however, of possible land grants that might be given to veterans after the war.

Crockett took an oath of allegiance to the Texas government on Jan. 12 in Nacogdoches and enlisted as a volunteer, as did his traveling companions. They marched off to war on Jan. 16 but had no orders telling them where to go. Davis speculates that Crockett likely was directed to see Houston, in a town further south, to get his orders.

Blow it up, surrender it or defend it?

There were two major routes for the Mexican army’s invasion of Texas, but each had a fort standing in the way. One was at Goliad; the other at San Antonia’s Alamo. In January 1836, the Alamo was short of men and supplies. Its commander told Houston in a Jan. 14 letter that the fort would be “easy prey to the enemy” unless reinforced.

On Jan. 17, Houston, thinking the Alamo indefensible, sent Bowie to San Antonio to dismantle the town’s fortifications.

That same day, Houston wrote a letter to the governor stating that he had "ordered the fortifications in the town of Bexar [San Antonio] to be demolished, and if you should think well of it, I will remove all the cannon and other munitions … blow up the Alamo, and abandon the place, as it will be impossible to keep up the Station with volunteers.” The “if you should think well of it” phrase indicates that Houston’s order to Bowie depended on the Texas government’s approval.

Bowie arrived at the Alamo on Jan. 18. After looking over the defenses, he decided it still held promise as a fort if strengthened and, considering its geographic position, should not be given up without a fight. While waiting for government approval to follow Houston’s demolition wishes, Bowie got to work improving the fortifications.

On Jan. 21, the governor ordered Travis to recruit volunteers to reinforce the Alamo, whose commanders learned the next day that Santa Anna was getting close to the Rio Grande. The Texas government on Jan. 31 turned down Houston’s request to destroy the fort.

In a Feb. 2 letter, Bowie asked the governor for more men and supplies. He wrote that the “salvation of Texas” depended on keeping San Antonio out of enemy hands, adding that “we will rather die in these ditches than give it up to the enemy."

Travis arrived on Feb. 3.

Crockett was also on his way to San Antonio. The reason is still something of a mystery. After leaving Nacogdoches, Crockett showed up Jan. 22-24 in Washington-on-the-Brazos, where he expected to find Houston, who was no longer there. In Washington he learned about the situation at San Antonio and the Mexican army’s approach.

Maybe someone other than Houston ordered him to San Antonio, “but he may just as possibly have been moving about entirely on his own initiative,” according to Davis. It is not certain when Crockett arrived at the Alamo, but sometime in the Feb.5-8 range is considered a good estimate.

Santa Anna’s troops entered San Antonio on Feb. 23 and prepared for a siege of the Alamo. Bowie sent a note to Santa Anna to see if the general wanted to “parley” on surrender terms. Santa Anna responded that he would not discuss terms for a surrender and said the rebels could save their lives only by placing themselves “immediately at the disposal” of the Mexican government.

To Travis that meant Santa Anna could decide what he wanted to do with the Texans after a surrender, including the possibility of executing at least the leaders. After another attempt to start negotiations, the Mexicans responded with their previous demands. Travis told them that if the Texans decided not to accept those terms, he would fire a cannon. He gave the order to fire the cannon.

The defense of the Alamo, as the historical record shows, was not irrational behavior by Bowie, Travis and Crockett. They had been directed by the Texas government to prepare for battle. The fort was a strategic roadblock worth defending if possible. When faced with overwhelming odds, the Alamo’s commanders considered the possibility of a negotiated surrender, but there is little reason to surrender if you are likely to be executed anyway.

Did Crockett buy time for Houston?

“The notion that the men of the Alamo died buying time for Sam Houston to build an army is well-entrenched in Alamo lore, but a review of Houston's activities shows it to be unfounded,” says R. Bruce Winders, Alamo historian and curator, in a paper titled “Alamo Myths and Misconceptions.”

After being named commander of the Texas army on Nov. 12, Houston’s first task was to send recruiters to raise an Army. He also had to round up weapons, uniforms and supplies. Because he had no troops officially under his command at the time, Houston took a leave of absence on Jan. 28 to deal with some personal business and negotiated a treaty with the Cherokees during that time.

Houston then served as a delegate to the Texas constitutional convention at Washington-on-the-Brazos. The delegates declared their independence from Mexico on March 2 (the defenders at the Alamo probably didn’t get the news but expected the declaration would be made). While at the convention, Houston was given authority over the volunteer units as well as the regular Texas army. Houston didn’t leave the convention until March 6.

By then it was too late to help the Alamo. During the tense months leading up to Santa Anna’s attack, Houston had spent much of his time on a leave of absence and attending the constitutional convention. After leaving the convention, he went to the town of Gonzales where a force of volunteers had come together. Combining them with troops of the regular Texas army, Houston defeated Santa Anna at San Jacinto on April 21, 1836.

Sources:

- Three Roads to the Alamo: The Lives and Fortunes of David Crockett, James Bowie, and William Barret Travis, by William C. Davis ( HarperCollins Publishers Inc., 1998)

- Alamo Myths and Misconceptions, by R. Bruce Winders, Alamo historian and curator.

- “Battle of the Alamo,” The Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association.

- Chronology: The Alamo.

He added that both men had Texas’ independence as a goal but adopted different tactics: “Davy Crockett said: ‘I think I will go to the Alamo.’ Some people said: ‘Davy, if you go to the Alamo, you will get killed.’ He went to the Alamo anyway and he did get killed, but we remember him for his bravery and we remember the Alamo.”

The senator said Houston had a better approach: “He withdrew with his men to San Jacinto. He was heavily criticized by some people in Texas at that time for withdrawing. Some said it was a retreat, but he waited until the Mexican General Santa Anna was in a siesta with his troops, he attacked, defeated his troops, and he won the war.”

The other candidate in the election, Joe Carr (who would lose the primary), defended Crockett against what he called an “insulting analogy” and praised him for “staying and fighting at the Alamo and heroically sacrificing his life for the principles Tennesseans believe in.” Carr added, “It was the bravery of Davy Crockett and thirty-one Tennesseans at the Alamo who gave their lives that allowed the time necessary for Sam Houston to recruit the men necessary to beat Santa Anna and the Mexican army.”

We pointed out that neither candidate had his history entirely correct, and in an email asked William Davis, author of Three Roads to the Alamo, if Crockett could have said, as Alexander quoted the frontiersman, “I think I will go the Alamo,” and ignored warnings that he would get killed?

Davis responded. “My guess would be that Alexander just made it up. No source says what he said.”

Related:

List: First permanent settlements in each state

Follow StudyHall.Rocks on Twitter.

If you would like to comment, give us a shout, or like us on Facebook and tell us what you think.