Mr. Lincoln's (diverse) neighborhood

In our time, city officials draft complex plans to encourage the development of neighborhoods that are welcoming to everyone: singles, families, the young, the old, a mix of ethnic groups and a variety of income levels.

But more than 150 years ago, Abraham Lincoln’s neighborhood in Springfield, Ill., was home to lawyers, businessmen, one entrepreneurial woman photographer, teachers, a bricklayer, a lawman and an African-American teamster deeply involved in the Underground Railroad.

Lincoln’s neighborhood reflected American ideals as much as his stirring speeches did.

Finding a home in Springfield

Born in Kentucky on Feb. 12, 1809, Lincoln went with his family to Indiana in 1816 and then to Illinois in 1830, settling near Decatur. The next year, 22-year-old Lincoln moved on his own to New Salem, where he worked in stores, was a postmaster and did surveying work. In 1834, he was elected to the Illinois House of Representatives, which met in Vandalia at the time but voted in 1837 to move the capital to Springfield.

Lincoln, who became a lawyer in 1836 and served in the Illinois House until 1842, moved to Springfield in April 1837 and shared a room with a store owner above the man’s shop. He married Mary Todd on Nov. 4, 1842. They took a room on the second floor of a boarding house, the Globe Tavern, where their first son, Robert, was born Aug. 1, 1843. The Lincolns rented a three-room cottage for the winter.

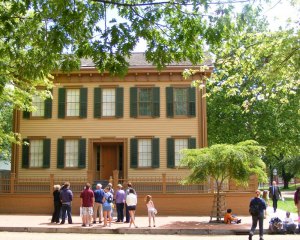

Lincoln bought a house at Eighth and Jackson streets for $1,500 on Jan. 16, 1844, and the family moved in May 1.

Lincoln would live there until he was elected president, except for the 1847-49 period, when he was in Washington as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Three sons were born in the house. Edward was born March 10, 1846, and died after an illness on Feb. 1, 1850. William, “Willie,” was born Dec. 21, 1850. Thomas, called “Tad” was born April 4, 1853.

The five-room, 1½-story building was expanded or renovated six times between 1846 and early 1860, ending up a two-story, 12-room structure. It was a big house, but not the biggest in Springfield. The house and its occupants became part of an interesting neighborhood.

Meet the neighbors

When the Lincolns left Springfield for the White House in early 1861, the city had a population of 9,320, which included large groups of Irish, German and Portuguese immigrants. There were 203 African-Americans living in the city, according to the 1860 census. Many blacks were homeowners. Others lived in the houses of their white employers.

Here are some of the Springfield residents who lived in a four-block square that included the Lincoln house. This information comes primarily from the Lincoln Home National Historic Site.

Jesse K. Dubois: a lawyer, staunch Republican and Illinois state auditor. He served with Lincoln in the state legislature and helped organize support for him during the 1860 Republican convention in Chicago that chose the party’s nominee for president.

George Shutt: a lawyer, staunch Democrat and Dubois’ next door neighbor. During the 1860 presidential campaign, he spoke at rallies for one of Lincoln’s opponents, Stephen A. Douglas.

Allen Miller: a wealthy businessman who sold leather, tinware and stoves.

Charles Corneau: a druggist.

Amos Worthen: An Illinois state geologist, he studied mineral resources and geological features in the state.

Francis Springer: a teacher and minister who ran a private school in his home and started an Evangelical Lutheran congregation. He moved in 1847 when he became president of a seminary in a neighboring county.

Charles Arnold: the purchaser of the Springer property; a carpenter, miller and politician, at various times county treasurer and county sheriff.

Jesse H. Kent: a carpenter and carriage-maker, elected municipal judge.

Henson Lyon: a retired farmer and land speculator whose farm was a couple of miles east of Springfield.

John Roll: a Springfield builder who purchased lots and constructed his house in the neighborhood. He sold the house in 1853, and it became a rental property.

Sarah Cook: a professional photographer and widow who became a renter in the former Roll house in 1860. She sublet some of the rooms.

Harriet Dean: a teacher who taught in her home. She was also a noted gardener. Her husband left in early 1849 for the California gold rush and returned in late 1850, apparently without any gold. He died not long afterward. She died in January 1860 at the Illinois State Hospital for the Insane.

Julia Sprigg: a German immigrant and widow who bought a house for herself and her children. Her daughter babysat the Lincoln boys.

Mary Remann: another widow. She rented part of the house to help pay her expenses.

Jared P. Irwin: a bricklayer who helped construct the state Capitol building.

William Beedle: a railroad fireman, a job that involved shoveling coal into a locomotive’s firebox to heat the boiler that generated steam to power the train.

Jameson Jenkins: a teamster, also known as a drayman, the term for someone who drove a horse-drawn wagon to haul goods and occasionally people. Jenkins was born in North Carolina in about 1810, perhaps as a slave. He was a free man at least by his mid-20s and moved to Indiana, where he got married and had a child before heading to Illinois. Jenkins bought a home a few lots down the street from Lincoln on Feb. 18, 1848.

Jenkins was an active participant in the Underground Railroad — the escape routes that enslaved blacks took from the South to the North and sometimes into Canada. The freedom seekers were often helped at points along the way by abolitionists and others, even though people who assisted escaped slaves were subject to imprisonment under federal law. Jenkins may have used his wagons to help escapees get to safe places. His exploits were publicized in 1850, after he helped a group of runaway slaves escape the hands of slave catchers, according to newspaper accounts of the time.

A decade later, early in the morning of Feb. 11, 1861, Jenkins drove a carriage to the Chenery House hotel in Springfield. President-elect Lincoln and his family had moved out of their Eighth Street house on Feb. 8 and were staying at the hotel before their train ride to Washington. Jenkins took Lincoln to the Great Western Railroad depot to catch the 8 a.m. train.

Before the train departed, Lincoln gave a short farewell speech to the crowd. It began with these words: “My friends — no one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe every thing. Here I have lived a quarter of a century, and have passed from a young to an old man. Here my children have been born, and one is buried. I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return.”

He never did.

Follow Chuck Springston on Twitter.

Like us on Facebook and tell us what you think.

Related:

Photo Gallery: Mr. Lincoln's neighborhood

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, Washington’s Mount Vernon linked