Labor Day: A long journey for workers' rights

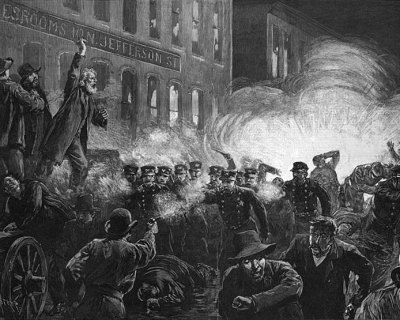

This engraving depicting the Haymarket riot by Thure de Thulstrup appeared in Harpers Weekly.

In the 19th century, concern about the rights of workers grew alongside the Industrial Age. Factory workers toiled long hours and often in difficult conditions. In 1866, the newly formed National Labor Union passed a resolution calling for an eight-hour day, according to the Library of Congress. The Illinois Legislature enacted a law setting an eight-hour day, but it was imperfect:

"On and after the first day of May 1867, eight hours of labor between the rising and the setting of the sun, in all mechanical trades, arts and employments and other cases of labor and service by the day, except farm employments, shall constitute and be a legal day's work, where there is no special contract or agreement to the contrary."

That last line -- "where there is no special contract or agreement to the contrary" -- delivered a magnificent loophole for employers.

In 1868, Congress approved an act making the workday eight hours for laborers, workmen and mechanics employed by the federal government. One year later, President Ulysses S. Grant signed a proclamation stating that "no reduction shall be made in the wages paid by the government by the day to such laborers, workmen, and mechanics on account of such reduction of the hours of labor." [See: The American Presidency Project, University of California: Ulysses S. Grant, proclamation on the eight-hour day, 1869.]

That covered the federal government -- but not private businesses. Tension over workers' rights continued. The most notable clash over the eight-hour workday occurred two decades later in Chicago.

An estimated 80,000 workers marched down Chicago’s Michigan Avenue on May 1, 1886. “This solidarity shocked some employers, who feared a workers' revolution, while others quickly signed agreements for shorter hours at the same pay,” recalls the Illinois Labor History Society on its website.

On May 4, workers meeting at Haymarket Square were attacked by police. Someone “threw the first dynamite bomb ever used in peacetime history of the United States,” the website recounts. “The police panicked, and in the darkness many shot at their own men.”

Seven policemen and four workers died. Eight men, all involved in the labor movement, were eventually arrested. Some taken into custody hadn’t even been present when the violence began. Four were hanged on Nov. 11, 1887. A fifth was found dead in his cell, his head half blown away by dynamite, the Illinois Labor History Society recounts. Three others were imprisoned.

After the riot, the eight-hour workday was viewed as “radical,” according to the Library of Congress.

In 1933, Congress passed the National Industrial Recovery Act, an attempt to help the country recover from the Great Depression. The act provided for the “establishment of maximum hours, minimum wages” and allowed unions to represent members in negotiations with an employer, the Library of Congress recounts.

In 1938, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act. “In its final form,” explains the U.S. Labor Department website, “the act applied to industries whose combined employment represented only about one-fifth of the labor force. In these industries, it banned oppressive child labor and set the minimum hourly wage at 25 cents, and the maximum workweek at 44 hours.”

Sources:

- The American Presidency Project, University of California: Ulysses S. Grant, proclamation on the eight-hour day, 1869.

- Encyclopedia of Chicago: Eight-Hour movement.

- Illinois Government website: Eight-hour workday law.

- Illinois Labor History Society: The Haymarket Affair.

- The Library of Congress: National Labor Union Requested an Eight-Hour Workday.

- Our Documents.gov: National Industrial Recovery Act.

- U.S. Department of Labor: Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

- U.S. Department of Labor: Labor Day History.

Related:

5 issues that divide employers and employees