What causes climate change?

Sadly, not all of our politicians understand. In January, as the new administration moved into Washington, the Environmental Protection Agency took down key portions of its website documenting how and why climate change is occurring. The EPA even took down a kid-friendly section used by students and teachers across the country.

We at StudyHall.Rocks believe it is essential for this information to stay before the public and remain accessible to students of all ages. To that end, we plan to publish the EPA's archived information.

Currently, the government's website explains that the site is being "updated" and offers a link to an archived snapshot dated Jan. 19. The complete EPA archive also can be viewed on the city of Chicago's website, as well as Internet Archive.org. Not all links on these websites are functional, however. As we run stories, we will do our best to add links and resources.

We welcome comments and suggestions (send an email or log onto our Facebook page).

Over time, we will do our best to re-create the bulk of this essential information in an easily accessible format. We'll start now, with the EPA's archived page on the causes of climate change.

What causes climate change: Earth's temperature depends on the balance between energy entering and leaving the planet’s system. When incoming energy from the sun is absorbed by the Earth system, Earth warms. When the sun’s energy is reflected back into space, Earth avoids warming. When absorbed energy is released back into space, Earth cools. Many factors, both natural and human, can cause changes in Earth’s energy balance, including:

- Variations in the sun's energy reaching Earth.

- Changes in the reflectivity of Earth’s atmosphere and surface.

- Changes in the greenhouse effect, which affects the amount of heat retained by Earth’s atmosphere.

These factors have caused Earth’s climate to change many times.

Scientists have pieced together a record of Earth’s climate, dating back hundreds of thousands of years (and, in some cases, millions or hundreds of millions of years), by analyzing a number of indirect measures of climate such as ice cores, tree rings, glacier lengths, pollen remains and ocean sediments, and by studying changes in Earth’s orbit around the sun.[2]

This record shows that the climate system varies naturally over a wide range of time scales. In general, climate changes prior to the Industrial Revolution in the 1700s can be explained by natural causes, such as changes in solar energy, volcanic eruptions and natural changes in greenhouse gas concentrations.[2] Recent climate changes, however, cannot be explained by natural causes alone. Research indicates that natural causes do not explain most observed warming, especially warming since the mid-20th century. Rather, it is extremely likely that human activities have been the dominant cause of that warming.[2]

Radiative Forcing: Radiative forcing is a measure of the influence of a particular factor (e.g. greenhouse gases, aerosols or land use changes) on the net change in Earth’s energy balance. On average, a positive radiative forcing tends to warm the surface of the planet, while a negative forcing tends to cool the surface.

Greenhouse gases have a positive forcing because they absorb energy radiating from Earth’s surface, rather than allowing it to be directly transmitted into space. This warms the atmosphere like a blanket. Aerosols or small particles can have a positive or negative radiative forcing, depending on how they absorb and emit heat or reflect light. For example, black carbon aerosols have a positive forcing since they absorb sunlight. Sulfate aerosols have a negative forcing since they reflect sunlight back into space.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Annual GHG (greenhouse gas) Index, which tracks changes in radiative forcing from greenhouse gases over time, shows that such forcing from human-added greenhouse gases has increased 27.5 percent between 1990 and 2009. Increases in carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere are responsible for 80 percent of the increase. The contribution to radiative forcing by methane (CH4) and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) has been nearly constant or declining, respectively, in recent years.

The greenhouse effect causes the atmosphere to retain heat: When sunlight reaches Earth’s surface, it can either be reflected back into space or absorbed by Earth. Once absorbed, the planet releases some of the energy back into the atmosphere as heat (also called infrared radiation). Greenhouse gases like water vapor (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), and methane (CH4) absorb energy, slowing or preventing the loss of heat to space. In this way, greenhouse gases act like a blanket, making Earth warmer than it would otherwise be. This process is commonly known as the “greenhouse effect.”

The role of the greenhouse effect in the past: Over the last several hundred thousand years, CO2 levels varied in tandem with the glacial cycles. During warm "interglacial" periods, CO2 levels were higher. During cool "glacial" periods, CO2 levels were lower.[2] The heating or cooling of Earth’s surface and oceans can cause changes in the natural sources and sinks of these gases, and thus change greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere.[2] These changing concentrations are thought to have acted as a positive feedback, amplifying the temperature changes caused by long-term shifts in Earth’s orbit.[2]

Feedbacks Can Amplify or Reduce Changes: Climate feedbacks amplify or reduce direct warming and cooling effects. They do not change the planet’s temperature directly. Feedbacks that amplify changes are called positive feedbacks. Feedbacks that counteract changes are called negative feedbacks. Feedbacks are associated with changes in surface reflectivity, clouds, water vapor and the carbon cycle.Water vapor appears to cause the most important positive feedback. As Earth warms, the rate of evaporation and the ability of air to hold water vapor both rise, increasing the amount of water vapor in the air. Because water vapor is a greenhouse gas, this leads to further warming.

The melting of Arctic sea ice is another example of a positive climate feedback. As temperatures rise, sea ice retreats. The loss of ice exposes the underlying sea surface, which is darker and absorbs more sunlight than ice, increasing the total amount of warming.

Some types of clouds cause a negative feedback. Warming temperatures can increase the amount or reflectivity of these clouds, reflecting more sunlight back into space, cooling the surface of the planet. Other types of clouds, however, contribute a positive feedback.

There are also several positive feedbacks that increase greenhouse gas concentrations. For example, as temperatures warm:

- Natural processes that are affected by warming, such as permafrost thawing, tend to release more CO2.

- The ocean releases CO2 into the atmosphere and absorbs atmospheric CO2 at a slower rate.

- Several types of land surfaces may release more methane (CH4).

These changes lead to higher concentrations of atmospheric greenhouse gases and contribute to increased warming.

The recent role of the greenhouse effect: Since the Industrial Revolution began around 1750, human activities have contributed substantially to climate change by adding CO2 and other heat-trapping gases to the atmosphere. These greenhouse gas emissions have increased the greenhouse effect and caused Earth’s surface temperature to rise. The primary human activity affecting the amount and rate of climate change is greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of fossil fuels.

The main greenhouse gases: The most important greenhouse gases directly emitted by humans include carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and several others. The sources and recent trends of these gases are detailed below.

Carbon dioxide: Carbon dioxide is the primary greenhouse gas that is contributing to recent climate change. CO2 is absorbed and emitted naturally as part of the carbon cycle, through plant and animal respiration, volcanic eruptions and ocean-atmosphere exchange. Human activities, such as the burning of fossil fuels and changes in land use, release large amounts of CO2, causing concentrations in the atmosphere to rise.

Atmospheric CO2 concentrations have increased by more than 40 percent since pre-industrial times, from approximately 280 parts per million by volume in the 18th century to over 400 parts per million by volume in 2015. The monthly average concentration at Mauna Loa (a volcano in Hawaii) now exceeds 400 parts per million by volume for the first time in human history. The current CO2 level is higher than it has been in at least 800,000 years.[2] Some volcanic eruptions released large quantities of CO2 in the distant past. However, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) reports that human activities now emit more than 135 times as much CO2 as volcanoes each year.

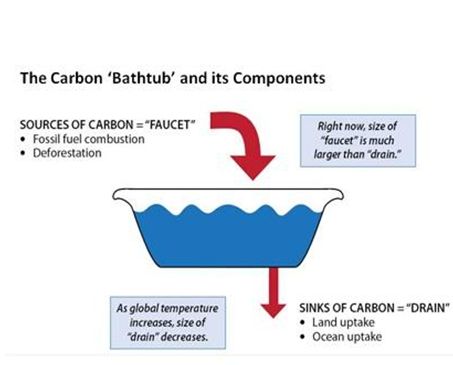

Human activities currently release more than 30 billion tons of CO2 into the atmosphere every year.[2] The resultant build-up of CO2 in the atmosphere is like a tub filling with water, where more water flows from the faucet than the drain can take away.

If the amount of water flowing into a bathtub is greater than the amount of water leaving through the drain, the water level will rise. CO2 emissions are like the flow of water into the world's carbon bathtub. Sources of CO2 emissions such as fossil fuel burning, cement manufacture and land use are like the bathtub's faucet. "Sinks" of CO2 in the ocean and on land (such as plants) that take up CO2 are like the drain. Today, human activities have turned up the flow from the CO2 "faucet," which is much larger than the "drain" can cope with, and the level of CO2 in the atmosphere (like the level of water in a bathtub) is rising.

Methane: Methane is produced through both natural and human activities. For example, natural wetlands, agricultural activities, and fossil fuel extraction and transport all emit CH4.

Methane is more abundant in Earth’s atmosphere now than at any time in at least the past 800,000 years.[2] Due to human activities, CH4 concentrations increased sharply during most of the 20th century and are now more than two-and-a-half times pre-industrial levels. In recent decades, the rate of increase has slowed considerably.[2]

Nitrous oxide: Nitrous oxide is produced through natural and human activities, mainly through agricultural activities and natural biological processes. Fuel burning and some other processes also create N2O. Concentrations of N2O have risen approximately 20 percent since the start of the Industrial Revolution, with a relatively rapid increase toward the end of the 20th century.[2] Overall, N2O concentrations have increased more rapidly during the past century than at any time in the past 22,000 years.[2]

Other greenhouse gases:

- Water vapor is the most abundant greenhouse gas and also the most important in terms of its contribution to the natural greenhouse effect, despite having a short atmospheric lifetime. Some human activities can influence local water vapor levels. However, on a global scale, the concentration of water vapor is controlled by temperature, which influences overall rates of evaporation and precipitation.[2] Therefore, the global concentration of water vapor is not substantially affected by direct human emissions.

- Tropospheric ozone (O3), which also has a short atmospheric lifetime, is a potent greenhouse gas. Chemical reactions create ozone from emissions of nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds from automobiles, power plants, and other industrial and commercial sources in the presence of sunlight. In addition to trapping heat, ground-level ozone is a pollutant that can cause respiratory health problems and damage crops and ecosystems.

- Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), together called F-gases, are often used in coolants, foaming agents, fire extinguishers, solvents, pesticides, and aerosol propellants. Unlike water vapor and ozone, these F-gases have a long atmospheric lifetime, and some of these emissions will affect the climate for many decades or centuries.

Other climate forcers: Particles and aerosols in the atmosphere can also affect climate. Human activities such as burning fossil fuels and biomass contribute to emissions of these substances, although some aerosols also come from natural sources such as volcanoes and marine plankton.

- Black carbon is a solid particle or aerosol, not a gas, but it also contributes to warming of the atmosphere. Unlike greenhouse gases, black carbon can directly absorb incoming and reflected sunlight in addition to absorbing infrared radiation. Black carbon can also be deposited on snow and ice, darkening the surface and thereby increasing the snow's absorption of sunlight and accelerating melt.

- Sulfates, organic carbon, and other aerosols can cause cooling by reflecting sunlight.

- Warming and cooling aerosols can interact with clouds, changing a number of cloud attributes such as their formation, dissipation, reflectivity, and precipitation rates. Clouds can contribute both to cooling, by reflecting sunlight, and warming, by trapping outgoing heat.

Changes in the sun’s energy affect how much energy reaches Earth’s system: Changes occurring in the sun itself can affect the intensity of the sunlight that reaches Earth’s surface. The intensity of the sunlight can cause either warming (during periods of stronger solar intensity) or cooling (during periods of weaker solar intensity). The sun follows a natural 11-year cycle of small ups and downs in intensity, but the effect on Earth’s climate is small.[1] Changes in the shape of Earth’s orbit as well as the tilt and position of Earth’s axis can also affect the amount of sunlight reaching Earth’s surface.[1][2]

The role of the sun’s energy in the past: Changes in the sun’s intensity have influenced Earth’s climate in the past. For example, the so-called “Little Ice Age” between the 17th and 19th centuries may have been partially caused by a low solar activity phase from 1645 to 1715, which coincided with cooler temperatures. The “Little Ice Age” refers to a slight cooling of North America, Europe, and probably other areas around the globe.[2] Changes in Earth’s orbit have had a big impact on climate over tens to hundreds of thousands of years. In fact, the amount of summer sunshine on the Northern Hemisphere, which is affected by changes in the planet’s orbit, appears to drive the advance and retreat of ice sheets. These changes appear to be the primary cause of past cycles of ice ages, in which Earth has experienced long periods of cold temperatures (ice ages), as well as shorter interglacial periods (periods between ice ages) of relatively warmer temperatures.[1][2]

The recent role of the sun’s energy: Changes in solar energy continue to affect climate. However, over the last 11-year solar cycle, solar output has been lower than it has been since the mid-20th century, and therefore does not explain the recent warming of the earth.[2] Similarly, changes in the shape of Earth’s orbit as well as the tilt and position of Earth’s axis affect temperature on very long timescales (tens to hundreds of thousands of years), and therefore cannot explain the recent warming.

Changes in reflectivity affect how much energy enters Earth’s system: When sunlight reaches Earth, it can be reflected or absorbed. The amount that is reflected or absorbed depends on Earth’s surface and atmosphere. Light-colored objects and surfaces, like snow and clouds, tend to reflect most sunlight, while darker objects and surfaces, like the ocean, forests, or soil, tend to absorb more sunlight.

The term albedo refers to the amount of solar radiation reflected from an object or surface, often expressed as a percentage. Earth as a whole has an albedo of about 30 percent, meaning that 70 percent of the sunlight that reaches the planet is absorbed.[3] Absorbed sunlight warms Earth’s land, water, and atmosphere.

Reflectivity is also affected by aerosols. Aerosols are small particles or liquid droplets in the atmosphere that can absorb or reflect sunlight. Unlike greenhouse gases, the climate effects of aerosols vary depending on what they are made of and where they are emitted. Those aerosols that reflect sunlight, such as particles from volcanic eruptions or sulfur emissions from burning coal, have a cooling effect. Those that absorb sunlight, such as black carbon (a part of soot), have a warming effect.

The role of reflectivity in the past: Natural changes in reflectivity, like the melting of sea ice, have contributed to climate change in the past, often acting as feedbacks to other processes.

Volcanoes have played a noticeable role in climate. Volcanic particles that reach the upper atmosphere can reflect enough sunlight back to space to cool the surface of the planet by a few tenths of a degree for several years.[2] These particles are an example of cooling aerosols. Volcanic particles from a single eruption do not produce long-term change because they remain in the atmosphere for a much shorter time than greenhouse gases.[2]

In addition, human activities have generally increased the number of aerosol particles in the atmosphere. Overall, human-generated aerosols have a net cooling effect offsetting about one-third of the total warming effect associated with human greenhouse gas emissions. Reductions in overall aerosol emissions can therefore lead to more warming. However, targeted reductions in black carbon emissions can reduce warming.[1]

References:

[1] USGCRP (2014). Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment. [Melillo, Jerry M., Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and Gary W. Yohe, Eds.] U.S. Global Change Research Program.

[2] IPCC (2013). Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

[3] NRC (2010). Advancing the Science of Climate Changes . National Research Council. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, USA.

Related:

EPA takes down climate change site for kids

Follow StudyHall.Rocks on Twitter.

If you would like to comment, give us a shout, or like us on Facebook and tell us what you think.