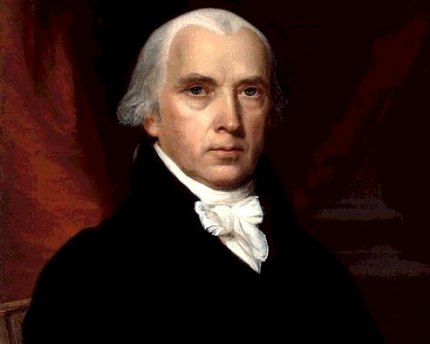

Madison: Father of the U.S. Constitution

In the administration of close friend and fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson, he served as secretary of state. He married the charming Dolley Payne Todd (1768-1849), a talented hostess who left an imprint as first lady.

As a two-term president (1809-17), Madison led the country through the War of 1812. And in a ranking of presidents by intelligence, he is placed second. Jefferson takes the top spot.

But Madison's legacy is first and foremost tied to the country's formative years, when he took a leading role in writing and promoting passage of the U.S. Constitution and subsequently the Bill of Rights. Here is how it happened, along with sources and links for further study.

About Madison: Raised on a plantation near the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, Madison was described as a sickly child who suffered "psychosomatic, or stress-induced, seizures, similar to epileptic fits that plagued him on and off throughout his youth," according to J.C.A. Stagg, professor of history at the University of Virginia. Even so, Madison was an avid reader, Stagg adds, on the website for the university's Miller Center. "By the time he entered the College of New Jersey, which later became Princeton University, Madison had mastered Greek and Latin under the direction of private tutors. He completed his college studies in two years but stayed on at Princeton for another term to tackle Hebrew and philosophy."

Madison also studied law. And in 1774 -- at only 23 years old -- he took his first post into public service, serving on the local Committee of Safety, which Stagg describes as a "patriot prorevolution group that oversaw the local militia."

After the American Revolution, the fledgling nation had operating problems: Following the Revolutionary War, the counry operated under the Articles of Confederation, but it wasn't going well. As designed, the central government was weak, points out the National Constitution Center. There were other problems too.

"In 1785 Maryland and Virginia differed on the matter of rights of navigation on the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay. A meeting on the question led to a general discussion of interstate commerce," according to Encyclopedia Britannica online. "As a result, the Virginia legislature called for a convention of all the states at Annapolis on September 11, 1786. However, with only five states represented, the convention decided that such questions could not be effectively dealt with unless the inadequacies of the Articles of Confederation were addressed."

Alexander Hamilton drafted a report proposing that a convention of all the states be held for that purpose.

Madison talks George Washington into attending: To iron out the wrinkles, delegates were to meet in Philadelphia in May 1787. At first, George Washington didn't want to go, recounts the website for Washington's home, Mount Vernon in Alexandria, Virginia.

Many citizens suspected the convention "would be merely a seizure of power from the states by an all-powerful, quasi-royal central government," the website explains. "Further, Washington initially refused to attend because he suspected that he would be made the Convention's leader, and probably be proposed as the nation's first chief executive. Washington did not want to be perceived as grasping for power, and active participation in the Convention—with its implied presidential caveat—could have been perceived as such by the public."

Madison got to work, and along with Gen. Henry Knox, he persuaded Washington to attend. "As strong believers in a more national system of government, each (Madison and Knox) believed that Washington needed to play a central role because of the great trust and respect he had accumulated during the War," the Mount Vernon website concludes. "With Madison's skillful personal courting, Washington agreed to attend."

Madison does his homework: Madison didn't just show up at the 1787 Constitutional Convention. He prepared for it.

He "drafted a document known as the Virginia Plan, which provided the framework for the Constitution of the United States," recounts the website for Madison's home in Virginia, Montpelier. Just 36 years old at the time, Madison "spent the months leading up to the convention in Montpelier’s library, studying many centuries of political philosophy and histories of past attempts at republican forms of government. His plan proposed a central government with three branches that would check and balance each other, keeping any one branch from wielding too much power."

It begins: Theoretically, the purpose of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia -- May-September 1787 -- was to amend the Articles of Confederation. But "the ultimate outcome was the proposal and creation of a completely new form of government," says the website for the National Constitution Center.

Madison led efforts supporting a strong central government. "His so-called Virginia Plan, submitted by Delegate Edmund Randolph, who was then governor of Virginia, became the essential blueprint for the Constitution that eventually emerged. Its major features included a bicameral national legislature with the lower house directly elected by the people, an executive chosen by the legislature, and an independent judiciary including a Supreme Court," writes Stagg of the University of Virginia.

But that wasn't all. Madison took notes -- and notes and notes and more notes.

In the front row, Madison "set bowed over his tablet, writing steadily," wrote Catherine Drinker Bowen in the book, Miracle at Philadelphia, The Story of the Constitutional Convention May to September 1787, (1966; Little Brown). "As a reporter, Madison was indefatigable, his notes comprehensive, set down without comment or aside. One marvels that he was able at the same time to take so large a part in the debates. It is true that in old age, Madison made some emendations in the record, to accord with various disparate notes which later came to light. ...Other members took notes at the convention …But these memoranda were brief, incomplete; had it not been for Madison we should possess very scanty records of the convention."

On Sept. 17, 1787, the Convention concluded with 38 out of 41 delegates present signing the new U.S. Constitution. It wouldn't take effect until nine out of 13 existing states ratified it.

Delaware became the first state to ratify the Constitution, on Dec. 7, 1787. On June 21, 1788, New Hampshire became the ninth of 13 states to ratify it, and the Constitution became the country's governmental blueprint.

The First Congress : As a representative from Virginia, Madison became a member of the First Congress, during which he drafted the first 10 amendments to the Constitution -- the Bill of Rights.

To Know More:

- The Complete Book of Presidents, by William A. DeGregorio and Sandra Lee Stuart, (Barricade Books; 2013).

- Encyclopedia Britannica: Annapolis Convention.

- George Washington's Mount Vernon: Constitutional Convention.

- James Madison's Montpelier: The Life of James Madison.

- Miracle at Philadelphia, The Story of the Constitutional Convention May to September 1787, (1966; Little Brown), by Catherine Drinker Bowen.

- National Constitution Center: Constitution FAQs.

- National Constitution Center: The day the Constitution was ratified.

- University of Virginia, Miller Center: James Madison, Life before the Presidency, by J.C.A. Stagg, professor of history at the University of Virginia.

- U.S. House of Representatives: Representative James Madison of Virginia.

- U.S. Library of Congress: James Madison's Contribution to the Constitution.

- U.S. Library of Congress: Madison's Memorable Wife.

- White House.gov: James Madison.

- White House History.org: Presidential portraits.

Related:

Ranking the presidents, best to worst

U.S. presidents ranked by intelligence

Quick Study: Who were the founding fathers?

If you would like to comment, like us on Facebook and tell us what you think.